Blog

Home > AgriFood Systems

ART OF LIVING HEALTHY

ART OF LIVING HEALTHY: IMPACT OF DIET DIVERSITY AND LIFESTYLE ON AGE REVERSAL & TELOMERES LENGTH (ART)

By CM Biradar, GGGC

In recent years, scientific research and ancient food wisdom have increasingly focused on the relationship between health and lifestyle factors and reversing or slowing the aging process. Particular attention has been paid to how our way of living (diets- more fruits and fresh produce, exercise, yoga, meditation, social, environment) can potentially slow down aging and promote overall health and wellness. One key area of interest is the effect of healthy eating habits and lifestyle choices on telomeres; the protective caps at the ends of our chromosomes play a crucial role in cellular ageing.

Healthy Foods and Aging

Health is a continuum of the soil, water, air, sunlight, flora and fauna, and everything is connected and caring in an integrated system. In the natural system, everything is in sync and synergy. So, how we grow food, diversity, culture, and nature are synch and symbiotic – restoring this union makes the food system sustainable, equitable, inclusive, and healthy [1]. Healthy foods grown under healthy conditions, such as healthy soil and an environment rich in nutrition, antioxidants, flavonoids, omega-3 fatty acids, and other nutrients, have been associated with slower ageing and longer telomeres. A study shows that those who consume good diets have longer telomeres compared to those who don’t [2], and consuming healthy food and balanced diets and diversity helps restore one health and plenty of health [3]. The diet’s high content of vegetables, fruits, nuts, and good fats (e.g., ghee, coconut and olive oil), may contribute to staying healthy and younger [4].

Exercise and Telomere Length

Regular physical activity has been shown to have a positive impact on health and telomere length. A meta-analysis published in the journal Ageing Reversal Research Reviews concluded that individuals who engaged in regular moderate to vigorous exercise had significantly longer telomeres compared to sedentary individuals [5].

Yoga and Meditation

Yoga and meditation, practices that combine physical postures, breathing techniques, and mindfulness, have also been linked to slower cellular aging. A study in the journal Cancer found that breast cancer survivors who practiced yoga had longer telomeres compared to those who didn’t [6]. Similarly, research published in Psychoneuroendocrinology showed that loving-kindness meditation was associated with longer telomeres in women [7].

Lifestyle Interventions and Telomerase Activity

Telomerase, the enzyme responsible for maintaining telomere length, can be influenced by lifestyle factors. A landmark study published in The Lancet Oncology, and Eat Lancets demonstrated that comprehensive lifestyle changes, including a plant-based diet, moderate exercise, stress management techniques, and social support, led to increased telomerase activities[8].

ART of Living Longer and Healthier

Age Reversal Therapy (ART) of living longer, healthier, and wealthier is deeply intertwined with the quality of our nutrition and lifestyle choices. By prioritizing organic, naturally grown foods under healthy soil and enviroment and integrating them with mindful practices like yoga and meditation, we may unlock the potential for extended healthspan – the period of life spent in good health.

While the field of Age Reversal Therapy (ART) is still evolving, the current evidence suggests that an organic, plant-rich diet combined with mindful lifestyle practices offers a promising path to longevity and wellness. As always, it’s important to consult with healthcare professionals when making significant changes to your diet or lifestyle.

While aging is a complex process influenced by various factors, including genetics, mounting evidence suggests that lifestyle choices can play a significant role in how we age at a cellular level. By adopting a healthy diet, engaging in regular exercise, and practicing stress-reduction techniques like yoga and meditation, individuals may be able to positively influence their telomere length and potentially slow down the aging process.

However, it’s important to note that while these diets and lifestyle factors show promise, more research is needed to fully understand their long-term effects on aging and overall health especially urban lifestyles where access to good food is still a challenge. Always consult with elders with food wisdom and healthcare professionals before making significant changes to your diets and lifestyle or starting new health regimens.

References

- Biradar, C., 2021. Innovations to integrate indigenous wisdom for better diet diversity and planetary health. UN Food Systems Summit 2021, Global Dialogues: Integrating Indigenous Knowledge with Emerging Technologies to Enhance Sustainability of Food System. 31 May, 2021, https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit

- Crous-Bou, M., et al. (2014). Mediterranean diet and telomere length in Nurses’ Health Study: population based cohort study. BMJ, 349, g6674.

- Biradar, C. 2021. Digital augmentation to support the agro-ecological transformation of agri-food systems in the drylands of Africa and Asia. In Agroecological transformation for sustainable food systems. Special France-CGIAR partnership. UN Food Systems Summit. Agropolis Internation. New York, September 2021.

- Biradar, C., Rizvi, J., & Dandin, S. (2022). Diversified farming systems for changing climate and consumerism. Journal of Horticultural Sciences, 17(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.24154/jhs.v17i1.2174

- Mundstock, E., et al. (2015). Effects of physical activity in telomere length: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 22, 72-80.

- Thaker, P. H., et al. (2013). Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nature Medicine, 12(8), 939-944.

- Hoge, E. A., et al. (2013). Loving-Kindness Meditation practice associated with longer telomeres in women. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 32, 159-163.

- Ornish, D., et al. (2013). Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study. The Lancet Oncology, 14(11), 1112-1120.

Transforming India’s Food and Land Systems for a Healthier Future

Transforming India’s Food and Land Systems for a Healthier Future

Insights from the High-Level Plenary on Enabling Sustainable and Resilient Food and Land Systems in India. By CM Biradar

In a world grappling with climate change and public health crises, India stands at a critical crossroads. The recent high-level plenary discussion on “Enabling Sustainable and Resilient Food and Land Systems in India” brought together experts, policymakers, and industry leaders to address one of the most pressing challenges of our time: how to create a food system that nourishes both our people and our planet.

The Interconnected Crisis: Land Degradation and Public Health

The plenary highlighted a stark reality: the health of India’s population is inextricably linked to the health of its land. Consider these sobering statistics:

- Nearly half of India’s population faces chronic health issues

- Every second Indian adult leads an inactive lifestyle (WHO, 2024)

- 147 million hectares of land are affected by degradation

- Over 35% of districts are experiencing groundwater depletion (225 of 700 districts)

These figures paint a picture of a nation where the decline in land health is mirrored by a decline in human health. With half of India’s workforce tied to food and land systems, the economic implications of this crisis are profound.

A Holistic Solution: Functional Agroecosystems and Agroforestry

The good news? We have a powerful solution at our fingertips. The plenary emphasized the potential of functional agroecosystems and agroforestry to address both land and human health simultaneously. This approach focuses on creating systems characterized by “five highs”:

- High Biodiversity: Integrating diverse crops, multifunctional trees and indigenous livestock to enhance ecosystem resilience and nutritional diversity.

- High Carbon in Land: Sequestering carbon in soil and biomass, combating climate change while improving soil fertility.

- High Water in Soil: Enhancing water retention, reducing runoff, and return of springsheds are crucial in a country facing severe water scarcity.

- High Productivity: Diversifying income streams and increasing yield stability in the face of climate uncertainties.

- High Equity: Creating year-round employment opportunities, particularly benefiting small farmers and women.

The Multiple Benefits of Transformation

By embracing functional agroecosystems, with focus on land, water and food in India stands to gain on multiple fronts:

- Environmental Restoration: Reversing land degradation and enhancing biodiversity.

- Climate Resilience: Increasing carbon sequestration and improving on-farm water management.

- Public Health: Providing diverse, nutritious foods and reducing exposure to synthetic agrochemicals.

- Economic Growth: Boosting agricultural productivity and creating new market opportunities to suite evolving new consumerism.

- Social Equity: Empowering rural communities, enhancing over system level resilience and reducing healthcare costs.

Charting the Path Forward

Implementing this vision will require a concerted effort across sectors. The plenary outlined a multi-pronged strategy:

- Policy Reforms: Incentivizing the transition to agroforestry and functional agroecosystems.

- Research and Innovation: Investing in locally-adapted models and exploring one-health and agrifood system transformation linkages.

- Education and Outreach: Training farmers and educating consumers about the benefits of diverse, local foods.

- Market Development: Creating sustainable value chains for agroforestry products and promoting functional foods.

A Call to Action

The transformation of India’s food and land systems is not just an environmental or agricultural initiative—it’s a comprehensive strategy for national health and prosperity. As we are heading towards grassroots level action for global change and Global Green Growth transition to reflect on the insights from this plenary, we’re more convinced than ever of the urgent need for action.

We call on policymakers, businesses, farmers, and citizens to unite behind this vision. By working together to implement functional agroecosystems and agroforestry practices, we can create a healthier, more resilient, and more prosperous India.

The path to a sustainable future is clear. It’s time to nurture our land, so it can nurture us in return. Join us in this crucial endeavor to transform India’s food and land systems—for the health of our nation and generations to come.

Moderated by Dr Ruchika Singh, Executive Program Director, Food, Land and Water, WRI India and Dr. Sampriti Baruah, Program Head, Sustainable Agriculture, Food, Land and Water, WRI India with distinguished panelists Ms. Yogita Rana, IAS, Joint Secretary, Department Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, and Director General, MANAGE, Hyderaba; Mr. Takayuki Hagiwara, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) Representative in India; Ms. Pritee Chaudhary, Regional Director, Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI); Padma Shri Reema Nanavaty, Director, Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA); and Dr. Chandrashekhar M. Biradar, Chairman and Managing Director, Global Green Growth Co. & Former Country Director-India CIFOR-ICRAF

KALPAVRIKSHA & KAMADHENU: Sacred Allies for Health, Heritage, and Functional Food Systems

KALPAVRIKSHA & KAMADHENU: Sacred Allies for Health, Heritage, and Functional Food Systems

Toward Functional Fats and Natural Farming for Nutrition and Natural Living

Dr. Chandrashekhar M. Biradar, c.biradar@gmail.com | January 15, 2024

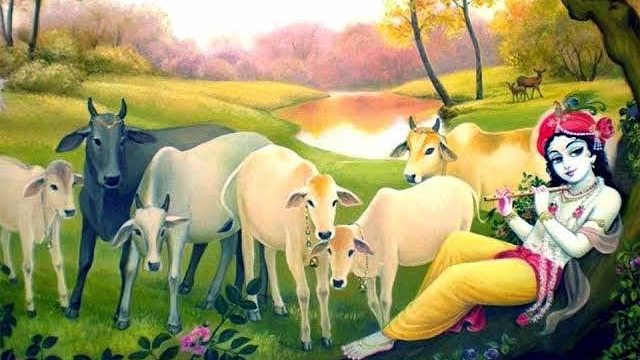

As India and much of the Global South face the converging crises of nutritional insecurity, ecological degradation, and climate instability, there is growing recognition of the value of reviving traditional, nature-aligned food systems. Rooted in ecological and ancient Indian wisdom and the holistic worldview of Sanatan Dharma, including the harmony of Pancha Mahabhutas (the five great elements: Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space), these systems offer time-tested approaches for restoring the health of both land and life.

Within this sacred ecology, two time-honoured and functionally significant elements stand out: virgin coconut oil derived from the Kalpavriksha (coconut tree), and desi cow ghee derived from Kamadhenu (indigenous cow). These are not just dietary ingredients—they are living expressions of a sustainable, regenerative food culture that nourishes the body, rejuvenates the soil, and strengthens rural livelihoods.These sacred species have long served as biocultural keystones across India. From the humid, coconut-rich coastal belts to the drought-prone drylands to mountains, the coconut tree and the indigenous cow have provided food, medicine, shelter, fuel, fiber, and spiritual sanctity. Their value systems are perennial, regenerative, and embedded in the household economy, community well-being, and ritual life.

Modern nutritional and biomedical science increasingly affirms what ancient Indian traditions have long upheld. Virgin coconut oil is exceptionally rich in medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), particularly lauric acid, which is also found in human breast milk. These MCTs are rapidly metabolized by the liver into energy, and have been shown to possess potent antimicrobial, antiviral, metabolic, and neuroprotective properties (St-Onge & Jones, 2002; Dayrit, 2015). The oil is also known for its digestive ease, immune support, and lipid-balancing effects, making it suitable for both therapeutic and culinary applications.

Similarly, desi cow ghee, especially when made using the traditional bilona (hand-churned) method from the milk of grass-fed cows, is a rich source of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate. Butyrate is known to support gut integrity, reduce inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and serve as a key energy source for colonocytes (Canani et al., 2011). Ghee also acts as an anupāna (carrier) in Ayurvedic medicine, enhancing the bioavailability of fat-soluble nutrients and herbal compounds (Lad, 1984; Mishra et al., 2021). Both coconut oil and ghee are naturally stable at high temperatures, free from harmful trans fats and oxidative degradation seen in industrially refined seed oils (Willett et al., 2019).

Beyond their health benefits, the production systems of Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu are rooted in ecological sustainability. Coconut palms thrive in mixed cropping systems, coastal and dryland agroforestry, and food forests, often with minimal irrigation and no synthetic inputs. Desi cows, when integrated into natural farming, enrich the system through cow dung, urine, ghee, curd, and milk, forming the Panchagavya suite used in seed treatment, soil inoculation, and pest management. Together, they contribute to closed-loop regenerative cycles, enhance soil organic carbon, support pollinators and biodiversity, and provide resilient income streams for smallholder farmers.

This paper explores the multidimensional value of Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu—their nutritional qualities, ecological roles, and economic significance—within the broader context of regenerative agriculture, functional food systems, and green livelihoods. By weaving together ancestral knowledge and contemporary science, these sacred species provide a living framework to restore health, regenerate landscapes, and reimagine food systems that are in balance with nature.

Scientific references supporting these insights include studies on the role of MCTs and lauric acid in health (St-Onge & Jones, 2002; Dayrit, 2015), gut health benefits of butyrate (Canani et al., 2011), and research on agroecological integration of perennial species and indigenous livestock (Mishra et al., 2021; FAO, 2021; ICAR, 2022). As we seek pathways toward climate resilience and nutrition equity, it becomes increasingly clear that the solutions may lie not in external innovations, but in reconnecting with the rooted wisdom of Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu.

Kalpavriksha: The Tree of Life and Functional Fat

The Coconut Tree (Cocos nucifera), traditionally referred to as Kalpavriksha in Indian scriptures, holds a unique place in both ecological and cultural landscapes. Literally meaning the “wish-fulfilling tree,” it has been celebrated for millennia in Indian coastal and island societies for its ability to provide nearly every essential need for human survival-food, drink, fuel, fiber, medicine, shelter, oil, sugar, and shade. In agroecological terms, it is a multipurpose perennial, deeply embedded in home gardens, coastal agroforestry systems, sacred groves, and temple precincts.

Modern science now affirms the nutritional, medicinal, and ecological importance of the coconut tree, especially the Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) extracted through cold-pressing of fresh coconut kernel. Recognized by nutritionists and medical researchers as a functional fat, VCO contains a unique profile of medium-chain fatty acids that differentiate it from most other plant-based oils, local resources, and year-round productivity, making it a sustainable and circular economic asset.

Nutritional Composition and Functional Properties

Virgin Coconut Oil consists of 92 percent saturated fats, of which over 60 percent are medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs). The most dominant MCT in coconut oil is lauric acid (C12:0), accounting for approximately 48 to 52 percentof its fatty acid content. Lauric acid is also the principal fatty acid found in human breast milk, known for its antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties (Dayrit, 2015; Enig, 2000).

Scientific studies have demonstrated the following key functional benefits of MCTs and lauric acid:

- Energy metabolism: MCTs are rapidly absorbed by the liver and converted into ketones, making them a quick and efficient source of energy. This property supports weight management, athletic performance, and cognitive function (St-Onge & Jones, 2002).

- Antimicrobial action: Lauric acid and its metabolite, monolaurin, have shown effectiveness against a range of pathogens including Helicobacter pylori, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and certain lipid-coated viruses like influenza and herpes (Shilling et al., 2013).

- Neurological support: Emerging studies indicate that coconut-derived MCTs may be beneficial in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease due to ketone production that supports neuronal energy metabolism (Fernando et al., 2015).

Known as the “Tree of Heaven,” Cocos nucifera or Coconut Tree is a cornerstone of coastal and tropical agroecosystems, revered for providing “everything needed for life.” The cold-pressed Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) derived from fresh coconut kernel is emerging as a scientifically validated functional fat.

Key Health Benefits of Virgin Coconut Oil

| Feature | Scientific Basis | Functional Benefit |

| Medium-Chain Triglycerides(MCTs) | Lauric acid (~50%) converts to ketones, fuels brain, boosts metabolism (St-Onge & Jones, 2002) | Energy, weight management, cognition |

| Antimicrobial Properties | Monolaurin fights pathogens including viruses, bacteria (Dayrit, 2015) | Immune system support, gut microbiome balance |

| Oxidative Stability | High smoke point (~175°C), low PUFA content (Seneviratne et al., 2009) | Safe for cooking without toxic byproducts |

| Ayurvedic & Folk Use | Used as Abhyanga oil, hair tonic, wound healer | Holistic health, skin & digestive wellness |

Virgin coconut oil aligns with indigenous knowledge systems that value minimal processing,

Virgin Coconut Oil vs Refined Oils

Unlike refined vegetable oils such as soybean, sunflower, or canola, which are often extracted using high heat and chemical solvents, VCO is extracted without heat or chemical treatment, thereby preserving its antioxidant compounds, polyphenols, and bioactive fats.

| Parameter | Virgin Coconut Oil | Refined Seed Oils |

| Extraction Method | Cold-pressed (no heat/solvent) | Solvent extraction (hexane, high heat) |

| Main Fatty Acids | MCTs (Lauric, Caprylic, Capric) | PUFA (Linoleic, Linolenic) |

| Smoke Point | ~175°C | 220°C (but unstable) |

| Shelf Stability | High (resists rancidity) | Low (oxidizes quickly) |

| Immune-Supporting Properties | Proven antimicrobial activity | No comparable benefit |

Ecological and Agronomic Value

From an agroecological perspective, coconut palms are drought-resilient, require minimal synthetic inputs, and support a wide range of intercropping systems including banana, cacao, pepper, yam, and fodder grasses. With proper management, a mature coconut palm can produce 50–100 coconuts per year for up to 60 years, offering a consistent and diversified livelihood for smallholders (APCC, 2019). Globally, India is the third largest producer of coconuts, after Indonesia and the Philippines, with an estimated production of 21 billion nuts annually across 2.1 million hectares (NHB, 2022). The southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh account for more than 90 percent of national production.

Each part of the tree is utilized:

- Nut: oil, milk, cream, pal-sugar, copra

- Husk: coir, mats, brushes, ropes

- Leaves: thatching, mats, handicrafts

- Wood: furniture, construction

- Sap: jaggery, vinegar, toddy

- Roots and shells: medicine, charcoal

Cultural and Ritual Significance

In Indian tradition, the coconut is offered in rituals and ceremonies as a symbol of purity, prosperity, and life. Breaking a coconut before a new beginning represents the shattering of ego and offering of self to the divine. In Ayurvedic formulations, coconut oil is used as a carrier for herbal oils, in abhyanga (therapeutic massage), and as a cooling agent in pitta-balancing treatments.

The ancient Sanskrit verse from the Kalpa Sutras praises:

नारिकेलं महाफलं त्रैलोक्ये फलमुत्तमम्

“Narikelaṁ mahāphalaṁ trailokye phalamuttamam”

“Among all fruits in the three worlds, coconut is considered the supreme.”

Tamil Cultural Proverb: புயலில் மகனை விட தேங்காய் முக்கியம்

“Puyalil maganai vida thengaai mukkiyam”

“In a storm, the coconut is considered more valuable than the son.” Literally meaning is if coconut tree is projected in storm, it protects the son (child) and family. This stark rural wisdom underscores the coconut’s role as a pillar of food, income, and life security.

“ಇಂಗು ತೆಂಗು ಇವೆರಡಿದ್ದರೆ, ಮಂಗವೂ ಅಡುಗೆ ಮಾಡಬಲ್ಲದು.”

“Ingu Tengu Iveradiddare, mangavu aduge madaballadu”

“Even a monkey can cook well if it has coconut and asafoetida.”

This rustic wisdom underscores the indispensable role of coconut and hing in traditional Indian cooking, not only for taste but also for nutrition, digestibility and health benefits.

Role in Sustainable Food Systems

Coconut-based farming systems are an integral component of regenerative and climate-resilient agriculture, especially in the coastal belts prone to saline intrusion, erratic rainfall, and market vulnerabilities. Integrated coconut farming with multi-tier crops and desi cattle ensures:

- Soil organic carbon buildup

- Enhanced pollination and biodiversity

- Improved water-use efficiency

- Diversified and year-round farm income

Coconut oil production also offers scope for green enterprise development through cold-pressed mills, value-added processing (virgin oil, flour, sugar, milk), and eco-friendly crafts from shell and coir.

Kamadhenu: The Sacred Cow and Golden Ghee

In the Sanatan Dharmic tradition, Kamadhenu—the divine, wish-fulfilling cow embodies the essence of abundance, nourishment, fertility, and ecological harmony. Described in ancient texts such as the Mahabharata and Puranas, Kamadhenu is not only a celestial being but also a symbolic representation of the Earth’s generosity and the regenerative power of life. In Indian rural life, this sacred symbol is reflected in the Desi (indigenous) cow, whose products are integral to food, farming, and spirituality. Among the most revered of these is ghee, especially when derived from indigenous cows using the traditional bilona method—a hand-churned, low-heat process that preserves the nutritional integrity and medicinal properties of the ghee. Far beyond a cooking medium, Desi Cow Ghee is considered a “life elixir” (amṛta) in Ayurveda and a vital ingredient in Panchagavya, Yajnas, Samskaras, and modern natural and regenerative farming practices.

Bullock and Millets are center of the logo the University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad

Key Health Benefits of Desi Cow Ghee

| Feature | Scientific Basis | Functional Benefit |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids(SCFAs) | Butyrate reduces gut inflammation, improves insulin response (Canani et al., 2011) | Colon health, anti-inflammatory, immunity |

| Carrier for Nutrients | Enhances absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, K | Better bioavailability of nutrients & herbs |

| Smoke Point | High (~250°C), suitable for deep cooking (Willett et al., 2019) | Safe, stable, and suitable for Indian cuisine |

| Ayurvedic Relevance | Considered Satvik and Anupana for Rasayanas | Spiritual and medicinal synergy |

Beyond consumption, cow ghee plays a critical role in soil enrichment (via Panchagavya), biopesticide formulation, and as a cultural cornerstone of farm-forest spiritual ecology.

Why Refined Seed Oils Fall Short

| Feature | Refined Seed Oils | Ghee / Coconut Oil |

| Extraction Method | Chemical solvents, high-heat processing | Cold-pressed or traditionally churned |

| Omega-6 to Omega-3 Ratio | ~20:1 (pro-inflammatory) | Balanced fatty acid profile |

| Oxidative Stability | Low (PUFA-rich, oxidizes quickly) | High (MCTs / SCFAs are stable) |

| Processing Additives | Deodorants, preservatives | None |

| Health Impact | Linked to metabolic disease (Simopoulos, 2002) | Supports gut, heart, cognitive health |

Thus, integrating ghee and coconut oil into functional food systems reclaims both health sovereignty and ecological resilience.

Nutritional Composition and Functional Properties

Desi cow ghee is predominantly composed of short-chain and medium-chain fatty acids (SCFAs and MCFAs), including butyrate, caproic, caprylic, and capric acids, which are rare in most vegetable oils.

| Nutrient Component | Quantity (per 100g) | Functional Role |

| Saturated fats | ~62–65% | Stability at high heat, energy source |

| Monounsaturated fats | ~25–28% | Heart and brain health |

| Butyric acid (Butyrate) | ~3–4% | Gut health, anti-inflammatory, colonocyte fuel |

| Omega-3 (ALA) | ~1% | Anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective |

| Vitamins A, D, E, K | 10–20% RDA/serving | Fat-soluble, boosts immunity & bone health |

| CLA (conjugated linoleic acid) | ~0.2–0.5% | Antioxidant, metabolic health |

(Sources: ICMR-NIN 2017; Mishra et al., 2021)

Scientific and Health Benefits

Modern biomedical research has affirmed many of the traditional claims regarding desi cow ghee:

- Gut Health and Immunity: Butyrate supports the integrity of intestinal lining, feeds beneficial microbiota, and reduces systemic inflammation (Canani et al., 2011; Hamer et al., 2008).

- Cardiovascular Health: Contrary to past beliefs, ghee from grass-fed cows has been shown to improve HDL cholesterol levels and reduce markers of inflammation (Mishra et al., 2021).

- Cognitive and Nervous System Support: Ghee acts as a brain tonic (medhya) in Ayurveda, and modern studies point to its neuroprotective antioxidant content.

- Heat Stability and Culinary Use: With a smoke point of around 250°C, ghee is one of the most stable fats for Indian cooking methods such as roasting and deep frying (Willett et al., 2019).

Traditional and Ritual Significance

In Vedic rituals, ghee is indispensable:

- Used in Yajnas and Homas: As an offering (Ahuti), ghee is considered a purifier and medium of transformation through fire (Agni), symbolizing the release of sattvic energy into the cosmos.

- Panchagavya: A blend of five products from the indigenous cow—milk, curd, ghee, dung, and urine—used for seed treatment, soil fertility, and detoxification rituals in both Ayurveda and natural farming.

- Anupāna in Ayurveda: Ghee acts as a vehicle to carry medicinal herbs deep into the tissues (dhatus) and across the blood-brain barrier (Lad, 1984; Sharma, 2018).

Ancient Ayurvedic texts such as Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita describe cow ghee as:

“सर्वेषां मेधसां श्रेष्ठं स्नेहनां च परं स्मृतम्।“

Sarveṣāṁ medhasāṁ śreṣṭhaṁ snehānāṁ ca paraṁ smṛtam

“Ghee is considered the best among all fats and supreme among brain tonics.”

Desi Cow vs Exotic Breeds: Nutritional and Ecological Advantage

Desi cow breeds such as Gir, Killara, Sahiwal, Tharparkar, Hallikar, and Malnad Gidda, etc have a unique beta-casein profile, and produce milk and ghee richer in CLA, SCFAs, and micronutrients compared to high-yielding exotic breeds.

| Trait | Desi Cow Ghee (A2) | Commercial Ghee (A1) |

| Butyrate content | High | Moderate to low |

| A2 beta-casein | Present | Absent or mixed (A1 dominant) |

| Digestibility | High | Can cause intolerance (in A1) |

| Ecological adaptability | High (low maintenance) | High-input systems needed |

| Role in mixed farming | Excellent | Limited |

(Sources: Singh et al., 2020; National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, ICAR)

Role in Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods

In natural and organic farming systems (e.g., Subhash Palekar’s ZBNF or Andhra Pradesh’s Community-Managed Natural Farming), desi cow ghee is a core input:

- Jeevamrutha: A fermented microbial inoculant made using ghee, dung, and jaggery that boosts soil microbial activity.

- Beejamrutha: Seed treatment with ghee-based formulations improves germination and disease resistance.

- Dung and urine: Provide nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and vital microbes—reducing dependency on chemical fertilizers.

Moreover, desi cow-based dairy enterprises contribute to women’s livelihoods, decentralized food processing, and climate-resilient circular economies with minimal ecological footprint.

Cultural Insight and Indigenous Wisdom

A traditional Sanskrit invocation states:

“कामधेनुं नमस्यामि सर्वकामार्थसिद्धये”

“I bow to Kamadhenu, who fulfills all righteous desires.”

In Indian folklore, the saying goes:“A house with a cow will never face hunger.”

This is not just sentiment—it reflects a functional ecosystem where food, fuel, manure, and medicine come from a single living being. Kamadhenu and the golden ghee she offers are not merely spiritual metaphors but real, regenerative assets that nourish soil, body, and society. In a world seeking climate-smart nutrition and ecological sustainability, Desi Cow Ghee stands as a biocultural bridge between ancient healing traditions and modern health science. Its reintegration into food systems, farming practices, and public health can play a key role in building a resilient, self-reliant, and sattvik Bharat.

Crops, trees and animals are the intergral part of the sustainable farming

Kalpavriksha & Kamadhenu in Sustainable Farming & Agroecology

These sacred species are not standalone nutrition sources. They are foundational pillars of natural farming, agroecology, and functional food forests.

| Agroecological Function | Coconut (Kalpavriksha) | Cow (Kamadhenu) |

| Soil Health | Litter biomass, water retention | Manure, urine, microbial inoculants |

| Biodiversity | Pollinator support, nesting sites | Livestock integration, pest control |

| Carbon Sequestration | Evergreen canopy, root mass | Grassland-cow synergy promotes SOC buildup |

| Rural Livelihoods | Oil, coir, toddy, fruit | Milk, ghee, compost, draft power |

| Cultural-Spiritual Significance | Used in rituals, weddings, festivals | Yajnas, Panchagavya, Gomaya, Gau Pooja |

Together, they represent living regenerative capital—yielding food, health, income, and culture in perpetuity.

Kamadhenu at the Gate of Abundance, and Kalpavriksha at the Door of Health

“A home with a cow and a coconut tree shall never go hungry.”

This age-old proverb is more than a rural belief—it is a time-tested blueprint for decentralized food security, functional nutrition, and natural capital regeneration.

They are not just sacred—they are strategic.

- They fit perfectly into Natural Farming, Nandi Krishi, Food Forests, Agroecology, Agroforestry, and Cow Sanctuary (Biradar, 2022)

- They empower smallholder women, self-help groups, and youth-based green enterprises.

- They deliver high Return on Regeneration (RoR) with minimal resource footprint.

Green Growth Perspective

| Parameter | Virgin Coconut Oil | Desi Cow Ghee |

| Yield/Tree or Cow | 100–150 nuts/year | 200–500 L milk/year |

| Processing Simplicity | Low-tech, decentralized units | Bilona method, local ghee units |

| Market Value (per Litre) | ₹300–500 | ₹800–1,200 |

| Ecological Footprint | Minimal (no irrigation, no chemicals) | Zero-waste (dung, urine, ghee, curd) |

| Carbon Balance | Negative (net sink) | Positive with dung-based biogas |

| Payback Period | 3–5 years (tree), 2–3 years (cow) | Recurring income after that |

Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu are not merely metaphors of abundance—they are living systems capable of addressing today’s crises of health, hunger, climate, and soil degradation.

Reintegrating Virgin Coconut Oil and Desi Cow Ghee into our farms, homes, and diets is an act of ecological restoration, nutritional reawakening, and cultural renewal. Let us reclaim these sacred systems—grounded in dharma and validated by data—for a swastha, samruddha, and satvik Bharat.

References

- Asia Pacific Coconut Community (APCC). (2019). Coconut Statistical Yearbook. Jakarta, Indonesia: APCC Secretariat.

- Canani, R. B., Di Costanzo, M., & Leone, L. (2011). Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 17(12), 1519–1528. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1519

- Dayrit, F. M. (2015). The properties of lauric acid and their significance in coconut oil. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 92(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-014-2562-7

- Enig, M. G. (2000). Know Your Fats: The Complete Primer for Understanding the Nutrition of Fats, Oils, and Cholesterol. Bethesda Press.

- FAO & UNEP. (2021). A Multi-Billion-Dollar Opportunity: Repurposing Agricultural Support to Transform Food Systems. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/publications

- FAO. (2021). The State of Food and Agriculture: Making Agrifood Systems More Resilient to Shocks and Stresses. Rome: FAO. https://www.fao.org/3/cb4476en/online/cb4476en.html

- Fernando, W. M. A. D. B., Martins, I. J., Goozee, K. G., Brennan, C. S., & Martins, R. N. (2015). The role of medium-chain triglycerides in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A review of human and animal studies. Aging Research Reviews, 20, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.12.003

- Hamer, H. M., Jonkers, D., Venema, K., Vanhoutvin, S., Troost, F. J., & Brummer, R. J. M. (2008). Review article: The role of butyrate on colonic function. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 27(2), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x

- ICAR. (2022). Natural Farming Comparative Research Trials: Annual Summary Report. New Delhi: Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

- ICMR-NIN. (2017). Indian Food Composition Tables 2017. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research.

- Lad, V. (1984). Ayurveda: The Science of Self-Healing. New Delhi: Lotus Press.

- Mishra, A., Kumar, A., & Shukla, A. (2021). Desi cow ghee: A functional food for health and wellness. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-021-00082-0

- National Horticulture Board (NHB). (2022). Horticultural Statistics at a Glance 2022. Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India. http://nhb.gov.in

- Sharma, R. K., & Dash, B. (2018). Charaka Samhita: Text with English Translation and Critical Exposition Based on Cakrapani Datta’s Ayurveda Dipika (Vol. 1–3). Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office.

- Shilling, M., Matt, L., Rubin, E., Visitacion, M. P., Haller, N. A., Grey, S. F., & Woolverton, C. J. (2013).Antimicrobial effects of virgin coconut oil and its medium-chain fatty acids on Clostridium difficile. Journal of Medicinal Food, 16(12), 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2012.0303

- Singh, R. R., Thakur, N., & Dubey, S. K. (2020). Characterization of A2 milk and comparative health effects. Indian Journal of Dairy Science, 73(6), 579–584. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-0563.2020.00106.2

- St-Onge, M. P., & Jones, P. J. H. (2002). Physiological effects of medium-chain triglycerides: Potential agents in the prevention of obesity. Journal of Nutrition, 132(3), 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/132.3.329

- Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., … & Murray, C. J. L. (2019).Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

- NBAGR–ICAR. (2022). Indigenous Livestock Breeds of India: Conservation and Utility. Karnal: National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

Sidebar