Blog

Home > News

KALPAVRIKSHA & KAMADHENU: Sacred Allies for Health, Heritage, and Functional Food Systems

KALPAVRIKSHA & KAMADHENU: Sacred Allies for Health, Heritage, and Functional Food Systems

Toward Functional Fats and Natural Farming for Nutrition and Natural Living

Dr. Chandrashekhar M. Biradar, c.biradar@gmail.com | January 15, 2024

As India and much of the Global South face the converging crises of nutritional insecurity, ecological degradation, and climate instability, there is growing recognition of the value of reviving traditional, nature-aligned food systems. Rooted in ecological and ancient Indian wisdom and the holistic worldview of Sanatan Dharma, including the harmony of Pancha Mahabhutas (the five great elements: Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space), these systems offer time-tested approaches for restoring the health of both land and life.

Within this sacred ecology, two time-honoured and functionally significant elements stand out: virgin coconut oil derived from the Kalpavriksha (coconut tree), and desi cow ghee derived from Kamadhenu (indigenous cow). These are not just dietary ingredients—they are living expressions of a sustainable, regenerative food culture that nourishes the body, rejuvenates the soil, and strengthens rural livelihoods.These sacred species have long served as biocultural keystones across India. From the humid, coconut-rich coastal belts to the drought-prone drylands to mountains, the coconut tree and the indigenous cow have provided food, medicine, shelter, fuel, fiber, and spiritual sanctity. Their value systems are perennial, regenerative, and embedded in the household economy, community well-being, and ritual life.

Modern nutritional and biomedical science increasingly affirms what ancient Indian traditions have long upheld. Virgin coconut oil is exceptionally rich in medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), particularly lauric acid, which is also found in human breast milk. These MCTs are rapidly metabolized by the liver into energy, and have been shown to possess potent antimicrobial, antiviral, metabolic, and neuroprotective properties (St-Onge & Jones, 2002; Dayrit, 2015). The oil is also known for its digestive ease, immune support, and lipid-balancing effects, making it suitable for both therapeutic and culinary applications.

Similarly, desi cow ghee, especially when made using the traditional bilona (hand-churned) method from the milk of grass-fed cows, is a rich source of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate. Butyrate is known to support gut integrity, reduce inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and serve as a key energy source for colonocytes (Canani et al., 2011). Ghee also acts as an anupāna (carrier) in Ayurvedic medicine, enhancing the bioavailability of fat-soluble nutrients and herbal compounds (Lad, 1984; Mishra et al., 2021). Both coconut oil and ghee are naturally stable at high temperatures, free from harmful trans fats and oxidative degradation seen in industrially refined seed oils (Willett et al., 2019).

Beyond their health benefits, the production systems of Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu are rooted in ecological sustainability. Coconut palms thrive in mixed cropping systems, coastal and dryland agroforestry, and food forests, often with minimal irrigation and no synthetic inputs. Desi cows, when integrated into natural farming, enrich the system through cow dung, urine, ghee, curd, and milk, forming the Panchagavya suite used in seed treatment, soil inoculation, and pest management. Together, they contribute to closed-loop regenerative cycles, enhance soil organic carbon, support pollinators and biodiversity, and provide resilient income streams for smallholder farmers.

This paper explores the multidimensional value of Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu—their nutritional qualities, ecological roles, and economic significance—within the broader context of regenerative agriculture, functional food systems, and green livelihoods. By weaving together ancestral knowledge and contemporary science, these sacred species provide a living framework to restore health, regenerate landscapes, and reimagine food systems that are in balance with nature.

Scientific references supporting these insights include studies on the role of MCTs and lauric acid in health (St-Onge & Jones, 2002; Dayrit, 2015), gut health benefits of butyrate (Canani et al., 2011), and research on agroecological integration of perennial species and indigenous livestock (Mishra et al., 2021; FAO, 2021; ICAR, 2022). As we seek pathways toward climate resilience and nutrition equity, it becomes increasingly clear that the solutions may lie not in external innovations, but in reconnecting with the rooted wisdom of Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu.

Kalpavriksha: The Tree of Life and Functional Fat

The Coconut Tree (Cocos nucifera), traditionally referred to as Kalpavriksha in Indian scriptures, holds a unique place in both ecological and cultural landscapes. Literally meaning the “wish-fulfilling tree,” it has been celebrated for millennia in Indian coastal and island societies for its ability to provide nearly every essential need for human survival-food, drink, fuel, fiber, medicine, shelter, oil, sugar, and shade. In agroecological terms, it is a multipurpose perennial, deeply embedded in home gardens, coastal agroforestry systems, sacred groves, and temple precincts.

Modern science now affirms the nutritional, medicinal, and ecological importance of the coconut tree, especially the Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) extracted through cold-pressing of fresh coconut kernel. Recognized by nutritionists and medical researchers as a functional fat, VCO contains a unique profile of medium-chain fatty acids that differentiate it from most other plant-based oils, local resources, and year-round productivity, making it a sustainable and circular economic asset.

Nutritional Composition and Functional Properties

Virgin Coconut Oil consists of 92 percent saturated fats, of which over 60 percent are medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs). The most dominant MCT in coconut oil is lauric acid (C12:0), accounting for approximately 48 to 52 percentof its fatty acid content. Lauric acid is also the principal fatty acid found in human breast milk, known for its antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties (Dayrit, 2015; Enig, 2000).

Scientific studies have demonstrated the following key functional benefits of MCTs and lauric acid:

- Energy metabolism: MCTs are rapidly absorbed by the liver and converted into ketones, making them a quick and efficient source of energy. This property supports weight management, athletic performance, and cognitive function (St-Onge & Jones, 2002).

- Antimicrobial action: Lauric acid and its metabolite, monolaurin, have shown effectiveness against a range of pathogens including Helicobacter pylori, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and certain lipid-coated viruses like influenza and herpes (Shilling et al., 2013).

- Neurological support: Emerging studies indicate that coconut-derived MCTs may be beneficial in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease due to ketone production that supports neuronal energy metabolism (Fernando et al., 2015).

Known as the “Tree of Heaven,” Cocos nucifera or Coconut Tree is a cornerstone of coastal and tropical agroecosystems, revered for providing “everything needed for life.” The cold-pressed Virgin Coconut Oil (VCO) derived from fresh coconut kernel is emerging as a scientifically validated functional fat.

Key Health Benefits of Virgin Coconut Oil

| Feature | Scientific Basis | Functional Benefit |

| Medium-Chain Triglycerides(MCTs) | Lauric acid (~50%) converts to ketones, fuels brain, boosts metabolism (St-Onge & Jones, 2002) | Energy, weight management, cognition |

| Antimicrobial Properties | Monolaurin fights pathogens including viruses, bacteria (Dayrit, 2015) | Immune system support, gut microbiome balance |

| Oxidative Stability | High smoke point (~175°C), low PUFA content (Seneviratne et al., 2009) | Safe for cooking without toxic byproducts |

| Ayurvedic & Folk Use | Used as Abhyanga oil, hair tonic, wound healer | Holistic health, skin & digestive wellness |

Virgin coconut oil aligns with indigenous knowledge systems that value minimal processing,

Virgin Coconut Oil vs Refined Oils

Unlike refined vegetable oils such as soybean, sunflower, or canola, which are often extracted using high heat and chemical solvents, VCO is extracted without heat or chemical treatment, thereby preserving its antioxidant compounds, polyphenols, and bioactive fats.

| Parameter | Virgin Coconut Oil | Refined Seed Oils |

| Extraction Method | Cold-pressed (no heat/solvent) | Solvent extraction (hexane, high heat) |

| Main Fatty Acids | MCTs (Lauric, Caprylic, Capric) | PUFA (Linoleic, Linolenic) |

| Smoke Point | ~175°C | 220°C (but unstable) |

| Shelf Stability | High (resists rancidity) | Low (oxidizes quickly) |

| Immune-Supporting Properties | Proven antimicrobial activity | No comparable benefit |

Ecological and Agronomic Value

From an agroecological perspective, coconut palms are drought-resilient, require minimal synthetic inputs, and support a wide range of intercropping systems including banana, cacao, pepper, yam, and fodder grasses. With proper management, a mature coconut palm can produce 50–100 coconuts per year for up to 60 years, offering a consistent and diversified livelihood for smallholders (APCC, 2019). Globally, India is the third largest producer of coconuts, after Indonesia and the Philippines, with an estimated production of 21 billion nuts annually across 2.1 million hectares (NHB, 2022). The southern states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh account for more than 90 percent of national production.

Each part of the tree is utilized:

- Nut: oil, milk, cream, pal-sugar, copra

- Husk: coir, mats, brushes, ropes

- Leaves: thatching, mats, handicrafts

- Wood: furniture, construction

- Sap: jaggery, vinegar, toddy

- Roots and shells: medicine, charcoal

Cultural and Ritual Significance

In Indian tradition, the coconut is offered in rituals and ceremonies as a symbol of purity, prosperity, and life. Breaking a coconut before a new beginning represents the shattering of ego and offering of self to the divine. In Ayurvedic formulations, coconut oil is used as a carrier for herbal oils, in abhyanga (therapeutic massage), and as a cooling agent in pitta-balancing treatments.

The ancient Sanskrit verse from the Kalpa Sutras praises:

नारिकेलं महाफलं त्रैलोक्ये फलमुत्तमम्

“Narikelaṁ mahāphalaṁ trailokye phalamuttamam”

“Among all fruits in the three worlds, coconut is considered the supreme.”

Tamil Cultural Proverb: புயலில் மகனை விட தேங்காய் முக்கியம்

“Puyalil maganai vida thengaai mukkiyam”

“In a storm, the coconut is considered more valuable than the son.” Literally meaning is if coconut tree is projected in storm, it protects the son (child) and family. This stark rural wisdom underscores the coconut’s role as a pillar of food, income, and life security.

“ಇಂಗು ತೆಂಗು ಇವೆರಡಿದ್ದರೆ, ಮಂಗವೂ ಅಡುಗೆ ಮಾಡಬಲ್ಲದು.”

“Ingu Tengu Iveradiddare, mangavu aduge madaballadu”

“Even a monkey can cook well if it has coconut and asafoetida.”

This rustic wisdom underscores the indispensable role of coconut and hing in traditional Indian cooking, not only for taste but also for nutrition, digestibility and health benefits.

Role in Sustainable Food Systems

Coconut-based farming systems are an integral component of regenerative and climate-resilient agriculture, especially in the coastal belts prone to saline intrusion, erratic rainfall, and market vulnerabilities. Integrated coconut farming with multi-tier crops and desi cattle ensures:

- Soil organic carbon buildup

- Enhanced pollination and biodiversity

- Improved water-use efficiency

- Diversified and year-round farm income

Coconut oil production also offers scope for green enterprise development through cold-pressed mills, value-added processing (virgin oil, flour, sugar, milk), and eco-friendly crafts from shell and coir.

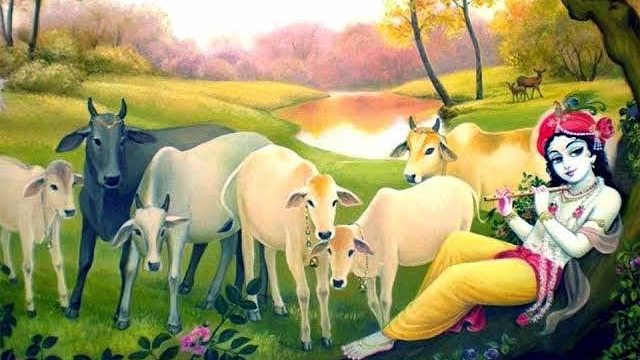

Kamadhenu: The Sacred Cow and Golden Ghee

In the Sanatan Dharmic tradition, Kamadhenu—the divine, wish-fulfilling cow embodies the essence of abundance, nourishment, fertility, and ecological harmony. Described in ancient texts such as the Mahabharata and Puranas, Kamadhenu is not only a celestial being but also a symbolic representation of the Earth’s generosity and the regenerative power of life. In Indian rural life, this sacred symbol is reflected in the Desi (indigenous) cow, whose products are integral to food, farming, and spirituality. Among the most revered of these is ghee, especially when derived from indigenous cows using the traditional bilona method—a hand-churned, low-heat process that preserves the nutritional integrity and medicinal properties of the ghee. Far beyond a cooking medium, Desi Cow Ghee is considered a “life elixir” (amṛta) in Ayurveda and a vital ingredient in Panchagavya, Yajnas, Samskaras, and modern natural and regenerative farming practices.

Bullock and Millets are center of the logo the University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad

Key Health Benefits of Desi Cow Ghee

| Feature | Scientific Basis | Functional Benefit |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids(SCFAs) | Butyrate reduces gut inflammation, improves insulin response (Canani et al., 2011) | Colon health, anti-inflammatory, immunity |

| Carrier for Nutrients | Enhances absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, K | Better bioavailability of nutrients & herbs |

| Smoke Point | High (~250°C), suitable for deep cooking (Willett et al., 2019) | Safe, stable, and suitable for Indian cuisine |

| Ayurvedic Relevance | Considered Satvik and Anupana for Rasayanas | Spiritual and medicinal synergy |

Beyond consumption, cow ghee plays a critical role in soil enrichment (via Panchagavya), biopesticide formulation, and as a cultural cornerstone of farm-forest spiritual ecology.

Why Refined Seed Oils Fall Short

| Feature | Refined Seed Oils | Ghee / Coconut Oil |

| Extraction Method | Chemical solvents, high-heat processing | Cold-pressed or traditionally churned |

| Omega-6 to Omega-3 Ratio | ~20:1 (pro-inflammatory) | Balanced fatty acid profile |

| Oxidative Stability | Low (PUFA-rich, oxidizes quickly) | High (MCTs / SCFAs are stable) |

| Processing Additives | Deodorants, preservatives | None |

| Health Impact | Linked to metabolic disease (Simopoulos, 2002) | Supports gut, heart, cognitive health |

Thus, integrating ghee and coconut oil into functional food systems reclaims both health sovereignty and ecological resilience.

Nutritional Composition and Functional Properties

Desi cow ghee is predominantly composed of short-chain and medium-chain fatty acids (SCFAs and MCFAs), including butyrate, caproic, caprylic, and capric acids, which are rare in most vegetable oils.

| Nutrient Component | Quantity (per 100g) | Functional Role |

| Saturated fats | ~62–65% | Stability at high heat, energy source |

| Monounsaturated fats | ~25–28% | Heart and brain health |

| Butyric acid (Butyrate) | ~3–4% | Gut health, anti-inflammatory, colonocyte fuel |

| Omega-3 (ALA) | ~1% | Anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective |

| Vitamins A, D, E, K | 10–20% RDA/serving | Fat-soluble, boosts immunity & bone health |

| CLA (conjugated linoleic acid) | ~0.2–0.5% | Antioxidant, metabolic health |

(Sources: ICMR-NIN 2017; Mishra et al., 2021)

Scientific and Health Benefits

Modern biomedical research has affirmed many of the traditional claims regarding desi cow ghee:

- Gut Health and Immunity: Butyrate supports the integrity of intestinal lining, feeds beneficial microbiota, and reduces systemic inflammation (Canani et al., 2011; Hamer et al., 2008).

- Cardiovascular Health: Contrary to past beliefs, ghee from grass-fed cows has been shown to improve HDL cholesterol levels and reduce markers of inflammation (Mishra et al., 2021).

- Cognitive and Nervous System Support: Ghee acts as a brain tonic (medhya) in Ayurveda, and modern studies point to its neuroprotective antioxidant content.

- Heat Stability and Culinary Use: With a smoke point of around 250°C, ghee is one of the most stable fats for Indian cooking methods such as roasting and deep frying (Willett et al., 2019).

Traditional and Ritual Significance

In Vedic rituals, ghee is indispensable:

- Used in Yajnas and Homas: As an offering (Ahuti), ghee is considered a purifier and medium of transformation through fire (Agni), symbolizing the release of sattvic energy into the cosmos.

- Panchagavya: A blend of five products from the indigenous cow—milk, curd, ghee, dung, and urine—used for seed treatment, soil fertility, and detoxification rituals in both Ayurveda and natural farming.

- Anupāna in Ayurveda: Ghee acts as a vehicle to carry medicinal herbs deep into the tissues (dhatus) and across the blood-brain barrier (Lad, 1984; Sharma, 2018).

Ancient Ayurvedic texts such as Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita describe cow ghee as:

“सर्वेषां मेधसां श्रेष्ठं स्नेहनां च परं स्मृतम्।“

Sarveṣāṁ medhasāṁ śreṣṭhaṁ snehānāṁ ca paraṁ smṛtam

“Ghee is considered the best among all fats and supreme among brain tonics.”

Desi Cow vs Exotic Breeds: Nutritional and Ecological Advantage

Desi cow breeds such as Gir, Killara, Sahiwal, Tharparkar, Hallikar, and Malnad Gidda, etc have a unique beta-casein profile, and produce milk and ghee richer in CLA, SCFAs, and micronutrients compared to high-yielding exotic breeds.

| Trait | Desi Cow Ghee (A2) | Commercial Ghee (A1) |

| Butyrate content | High | Moderate to low |

| A2 beta-casein | Present | Absent or mixed (A1 dominant) |

| Digestibility | High | Can cause intolerance (in A1) |

| Ecological adaptability | High (low maintenance) | High-input systems needed |

| Role in mixed farming | Excellent | Limited |

(Sources: Singh et al., 2020; National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, ICAR)

Role in Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods

In natural and organic farming systems (e.g., Subhash Palekar’s ZBNF or Andhra Pradesh’s Community-Managed Natural Farming), desi cow ghee is a core input:

- Jeevamrutha: A fermented microbial inoculant made using ghee, dung, and jaggery that boosts soil microbial activity.

- Beejamrutha: Seed treatment with ghee-based formulations improves germination and disease resistance.

- Dung and urine: Provide nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and vital microbes—reducing dependency on chemical fertilizers.

Moreover, desi cow-based dairy enterprises contribute to women’s livelihoods, decentralized food processing, and climate-resilient circular economies with minimal ecological footprint.

Cultural Insight and Indigenous Wisdom

A traditional Sanskrit invocation states:

“कामधेनुं नमस्यामि सर्वकामार्थसिद्धये”

“I bow to Kamadhenu, who fulfills all righteous desires.”

In Indian folklore, the saying goes:“A house with a cow will never face hunger.”

This is not just sentiment—it reflects a functional ecosystem where food, fuel, manure, and medicine come from a single living being. Kamadhenu and the golden ghee she offers are not merely spiritual metaphors but real, regenerative assets that nourish soil, body, and society. In a world seeking climate-smart nutrition and ecological sustainability, Desi Cow Ghee stands as a biocultural bridge between ancient healing traditions and modern health science. Its reintegration into food systems, farming practices, and public health can play a key role in building a resilient, self-reliant, and sattvik Bharat.

Crops, trees and animals are the intergral part of the sustainable farming

Kalpavriksha & Kamadhenu in Sustainable Farming & Agroecology

These sacred species are not standalone nutrition sources. They are foundational pillars of natural farming, agroecology, and functional food forests.

| Agroecological Function | Coconut (Kalpavriksha) | Cow (Kamadhenu) |

| Soil Health | Litter biomass, water retention | Manure, urine, microbial inoculants |

| Biodiversity | Pollinator support, nesting sites | Livestock integration, pest control |

| Carbon Sequestration | Evergreen canopy, root mass | Grassland-cow synergy promotes SOC buildup |

| Rural Livelihoods | Oil, coir, toddy, fruit | Milk, ghee, compost, draft power |

| Cultural-Spiritual Significance | Used in rituals, weddings, festivals | Yajnas, Panchagavya, Gomaya, Gau Pooja |

Together, they represent living regenerative capital—yielding food, health, income, and culture in perpetuity.

Kamadhenu at the Gate of Abundance, and Kalpavriksha at the Door of Health

“A home with a cow and a coconut tree shall never go hungry.”

This age-old proverb is more than a rural belief—it is a time-tested blueprint for decentralized food security, functional nutrition, and natural capital regeneration.

They are not just sacred—they are strategic.

- They fit perfectly into Natural Farming, Nandi Krishi, Food Forests, Agroecology, Agroforestry, and Cow Sanctuary (Biradar, 2022)

- They empower smallholder women, self-help groups, and youth-based green enterprises.

- They deliver high Return on Regeneration (RoR) with minimal resource footprint.

Green Growth Perspective

| Parameter | Virgin Coconut Oil | Desi Cow Ghee |

| Yield/Tree or Cow | 100–150 nuts/year | 200–500 L milk/year |

| Processing Simplicity | Low-tech, decentralized units | Bilona method, local ghee units |

| Market Value (per Litre) | ₹300–500 | ₹800–1,200 |

| Ecological Footprint | Minimal (no irrigation, no chemicals) | Zero-waste (dung, urine, ghee, curd) |

| Carbon Balance | Negative (net sink) | Positive with dung-based biogas |

| Payback Period | 3–5 years (tree), 2–3 years (cow) | Recurring income after that |

Kalpavriksha and Kamadhenu are not merely metaphors of abundance—they are living systems capable of addressing today’s crises of health, hunger, climate, and soil degradation.

Reintegrating Virgin Coconut Oil and Desi Cow Ghee into our farms, homes, and diets is an act of ecological restoration, nutritional reawakening, and cultural renewal. Let us reclaim these sacred systems—grounded in dharma and validated by data—for a swastha, samruddha, and satvik Bharat.

References

- Asia Pacific Coconut Community (APCC). (2019). Coconut Statistical Yearbook. Jakarta, Indonesia: APCC Secretariat.

- Canani, R. B., Di Costanzo, M., & Leone, L. (2011). Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 17(12), 1519–1528. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1519

- Dayrit, F. M. (2015). The properties of lauric acid and their significance in coconut oil. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 92(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11746-014-2562-7

- Enig, M. G. (2000). Know Your Fats: The Complete Primer for Understanding the Nutrition of Fats, Oils, and Cholesterol. Bethesda Press.

- FAO & UNEP. (2021). A Multi-Billion-Dollar Opportunity: Repurposing Agricultural Support to Transform Food Systems. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/publications

- FAO. (2021). The State of Food and Agriculture: Making Agrifood Systems More Resilient to Shocks and Stresses. Rome: FAO. https://www.fao.org/3/cb4476en/online/cb4476en.html

- Fernando, W. M. A. D. B., Martins, I. J., Goozee, K. G., Brennan, C. S., & Martins, R. N. (2015). The role of medium-chain triglycerides in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A review of human and animal studies. Aging Research Reviews, 20, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.12.003

- Hamer, H. M., Jonkers, D., Venema, K., Vanhoutvin, S., Troost, F. J., & Brummer, R. J. M. (2008). Review article: The role of butyrate on colonic function. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 27(2), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x

- ICAR. (2022). Natural Farming Comparative Research Trials: Annual Summary Report. New Delhi: Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

- ICMR-NIN. (2017). Indian Food Composition Tables 2017. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research.

- Lad, V. (1984). Ayurveda: The Science of Self-Healing. New Delhi: Lotus Press.

- Mishra, A., Kumar, A., & Shukla, A. (2021). Desi cow ghee: A functional food for health and wellness. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-021-00082-0

- National Horticulture Board (NHB). (2022). Horticultural Statistics at a Glance 2022. Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India. http://nhb.gov.in

- Sharma, R. K., & Dash, B. (2018). Charaka Samhita: Text with English Translation and Critical Exposition Based on Cakrapani Datta’s Ayurveda Dipika (Vol. 1–3). Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office.

- Shilling, M., Matt, L., Rubin, E., Visitacion, M. P., Haller, N. A., Grey, S. F., & Woolverton, C. J. (2013).Antimicrobial effects of virgin coconut oil and its medium-chain fatty acids on Clostridium difficile. Journal of Medicinal Food, 16(12), 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2012.0303

- Singh, R. R., Thakur, N., & Dubey, S. K. (2020). Characterization of A2 milk and comparative health effects. Indian Journal of Dairy Science, 73(6), 579–584. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-0563.2020.00106.2

- St-Onge, M. P., & Jones, P. J. H. (2002). Physiological effects of medium-chain triglycerides: Potential agents in the prevention of obesity. Journal of Nutrition, 132(3), 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/132.3.329

- Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., … & Murray, C. J. L. (2019).Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

- NBAGR–ICAR. (2022). Indigenous Livestock Breeds of India: Conservation and Utility. Karnal: National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

Role of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) in India’s Agri-Food System Transformation

Role of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) in India’s Agri-Food System Transformation

India stands at a critical juncture in its agrarian journey. Despite being the world’s largest producer of milk, pulses, and spices, and a global agricultural powerhouse, the average Indian farmer remains trapped in a cycle of low income, high risk, and uncertain futures. With over 86% of cultivators being small and marginal farmers, and millions more working as landless farm laborers, the promise of rural prosperity remains largely unfulfilled.

In this context, Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) emerged as a bold institutional innovation—intended to democratize access to markets, services, capital, and technology. They were envisioned not just as collectives, but as the new rural enterprise model to transform agriculture into a viable and dignified livelihood.

A growing perception questions their effectiveness—“Are FPOs a failed experiment?”

Even worse, many now see FPOs as mere input dealers or subsidy channels, far removed from the original vision of agrarian transformation.

It is time to confront this challenge honestly—and reframe the discourse.

Karnataka’s Center for Excellence for FPOs: A National First in Farmer-Led Transformation

The Government of Karnataka has established India’s first state-level Center for Excellence for Farmer Producer Organizations (CoE-FPO), a pioneering initiative designed to go beyond FPO formation and focus on long-term empowerment, market integration, and professional governance of farmer collectives.

Unlike traditional scheme-based support, this Center serves as a dedicated ecosystem enabler, offering capacity building, market and financial linkages, digital tools, and innovation incubation for FPOs across the state. It aims to transform FPOs from input retailers into vibrant rural enterprises that serve smallholders, promote regenerative agriculture, and build resilient value chains.

By creating this institution, Karnataka has set a national benchmark in agrarian reform—placing farmers at the center of enterprise, policy, and sustainability.

The FPOs as Instruments of Reform

The idea behind FPOs was simple yet powerful:

- Collectivize smallholders and workers to overcome scale disadvantages

- Enhance market access and bargaining power

- Promote value addition, branding, and enterprise development

- Create decentralized, farmer-led institutions that can anchor rural development

If implemented well, FPOs could play multiple roles:

- As economic engines for farmer income enhancement

- As social institutions for equity and inclusion (women, SC/ST, landless)

- As ecological stewards for sustainable and climate-resilient farming

Why FPOs Are Struggling: Systemic Challenges

Despite the noble intent, most FPOs remain trapped below the ₹1 crore turnover threshold. This is not because the model is flawed, but because the ecosystem around it is underdeveloped.

1. Top-Down Formation Without True Ownership

Most FPOs were formed to meet scheme targets, not farmer needs. Without grassroots participation or sustained handholding, they lack purpose and direction.

2. Weak Governance and Leadership

Board members often lack the training or business acumen needed to manage operations, ensure compliance, and make market-driven decisions.

3. Input Agency Trap

Many FPOs rely heavily on selling fertilizers, seeds, and pesticides—often under pressure from state schemes or private suppliers. This leads to short-term income but long-term stagnation, as they fail to build value chains or diversify services.

4. Lack of Market Orientation

Without reliable buyers or value addition, FPOs sell back into the same exploitative markets they were meant to escape—especially mandis and middlemen.

5. Limited Financial and Technological Infrastructure

Working capital, risk instruments, digital tools, and credit access remain weak. This limits scale, profitability, and ability to serve farmer members effectively.

Making FPOs Work for Smallholders and Farm Workers

Instead of abandoning the FPO model, we must course-correct and reform it—transforming FPOs from passive agents to active architects of India’s rural future.

1. Design for Farmers, Not for Forms

FPOs must be rooted in the needs and aspirations of their members. Priority should be given to:

- Inclusivity (women, youth, farm workers)

- Democratic governance and transparency

- Participatory planning and periodic training

2. Go Beyond Inputs—Become Rural Service Enterprises

FPOs should offer a full spectrum of services:

- Input retail + custom hiring + advisory

- Aggregation + processing + branding + marketing

- Digital payment systems, traceability, and real-time price intelligence

- Green economy services: composting, carbon farming, biodiversity credits

3. Invest in Market Linkages and Branding

FPOs should shift from being price takers to value makers by:

- Partnering with retail chains, exporters, processors, and digital platforms like ONDC, GeM, and eNAM

- Investing in storage, cold chains, and grading infrastructure

- Building FPO-level brands for local and global visibility

4. Enable Financial Inclusion and Risk Mitigation

Support from banks, NABARD, and fintechs must include:

- Working capital at affordable rates

- Insurance products and credit guarantees

- App-based accounting, dashboards, and compliance tools

5. Converge with National Missions and Green Growth

FPOs can serve as nodal institutions for:

- Natural farming and regenerative agriculture missions

- PM-FME, PM-KUSUM, and rural skilling programs

- Carbon and biodiversity markets, ESG funds, and circular economy projects

The Bigger Picture: FPOs as Pillars of Agrarian Renewal

When reimagined and revitalized, FPOs can play a central role in transforming India’s rural economy:

| Function | Impact |

| Collective Production | Scale efficiency and reduced cost of inputs |

| Value Chain Integration | Capture more of the consumer rupee |

| Green Transition | Carbon neutrality, biodiversity, and climate resilience |

| Livelihood Diversification | Employment for youth and farm workers |

| Institutional Convergence | Link to health, nutrition, and social security schemes |

Mindset Shift: From Projects to Enterprises

We must stop treating FPOs as one-off projects for subsidy disbursement and start treating them as farmer-owned, professionally-run rural enterprises.

An FPO is not a cooperative of the past—it is a 21st-century social business, one that can:

- Stabilize farmer incomes

- Revitalize degraded landscapes

- Empower marginalized communities

- Rebuild trust in agriculture as a dignified profession

Case Study: Grape Growers’ Collective Action– A Model of Informal Producers’ Organization (IPO)

From Solo Struggles to Collective Strength: How Informal Collaboration Reduced Input Costs for Grape Farmers

In the arid belts of North Karnataka, grape cultivation has been a long-standing livelihood for many smallholder farmers. Despite good yields and consistent efforts, the economic returns for these grape growers have been stagnating, causing distress and uncertainty.

During a field visit and interaction with a group of grape growers in the region, a harsh reality surfaced: while the cost of cultivation had increased nearly 300 times over the years, the selling price of grapes—whether fresh or dried—had remained the same or even declined due to market fluctuations.

Challenge Identified

On deeper inquiry, two primary cost drivers emerged:

- High Cost of Agrochemicals

Farmers were spending disproportionately on synthetic inputs—fertilizers, pesticides, fungicides, and plant growth regulators. - Irrigation-Related Expenses

Drippers, pumps, and sprinklers added significantly to capital and recurring costs.

Additionally, input procurement practices were inefficient:

- Farmers purchased inputs individually from city retailers.

- Each farmer made separate trips, losing a day’s work and incurring transport costs.

- Due to lack of volume, they had zero bargaining power and ended up paying 10–15 times (and in some cases up to 30 times) more than wholesale prices.

Intervention

A simple yet transformative suggestion was made:

“Why not come together as a group and coordinate input procurement collectively?”

The farmers were guided to form an informal producers’ group—not a formal FPO, but a voluntary, trust-based working collective.

Key steps:

- Identifying a Trusted Volunteer

One literate and trustworthy farmer from the group was nominated as a coordinator. - Needs Assessment

The coordinator collected input requirements from each member farmer (quantities, types, urgency, etc.). - Market Discovery and Vendor Engagement

The group invited quotations from various suppliers and negotiated for bulk discounts. - Direct Village-Level Delivery

The selected vendor agreed to deliver directly to the village, saving transport and time.

Outcomes

The results were immediate and significant:

- Farmers saved 25–30% on input costs through negotiated bulk discounts.

- Time savings were substantial—no more individual city trips, lost labor days, or dependency on transport.

- The process built trust, transparency, and collective learning among the farmers.

- Local employment was indirectly supported, as youth assisted in coordination and unloading activities.

- The model proved that trust-based informal producer networks can be economically effective and operationally agile.

Key Lessons

- Collective Farming Does Not Require Formality

Even without registration or legal formation, small groups of farmers can act as de facto producer organizations and enjoy similar benefits. - Local Leadership and Trust Are Critical

Identifying a committed and transparent coordinator is the backbone of informal collectivization. - Aggregation Unlocks Bargaining Power

The shift from individual to group procurement transformed the farmer’s role from price taker to price negotiator. - Replicability and Scalability

This informal model can be applied across crops and regions, particularly in input-intensive systems like grapes, pomegranate, banana, and vegetables.

Implications for Policy and Agrarian Reform

This case reveals that small, decentralized producer groups, even when informal, can serve as the foundation for low-cost, farmer-led value chain transformation. It offers a bottom-up pathway to:

- Reduce cost of cultivation

- Improve farm economics

- Build rural social capital

- Prepare the ground for formal FPO evolution, if desired

Rather than pushing for formality first, agrarian reform efforts should recognize and support such informal producer innovations—through mentorship, access to market data, digital tools, and linkages with extension services.

This simple act of collectivizing input demand changed the equation for a community of grape farmers. It is a living model of cooperative action without formal structures—rooted in trust, guided by common interest, and leading toward true economic empowerment.

Such stories remind us: agrarian reform doesn’t always need policy first—it often begins with people.

FPOs Are Not the Problem-They Are the Platform

The issue is not that FPOs have failed, but that we have yet to fully equip them with the right policy frameworks, patient capital, institutional handholding, and farmer-first governance they need to flourish.

Rather than reducing FPOs to mere “input agents,” we must reposition them as the backbone of India’s rural and agrarian renewal, platforms that enable equitable growth, regenerative farming, dignified livelihoods, and market integration for smallholders and farm workers alike.

With the right reforms and ecosystem support, India has the potential to nurture 10,000 thriving, future-fit FPOs, each not only serving its members, but strengthening the economic, ecological, and social foundation of the nation.

Forest Research So Far: Way Forward

‘Forest Research So Far : Way Forward’

The conference aims to gather comprehensive feedback from diverse stakeholders, including state forest departments, academic institutions, wood-based industries, and farming communities, on the current state of forestry research and its future direction. It will assess the effectiveness of existing research, identify critical gaps, and explore innovative strategies to address merging challenges in the forestry sector. The conference seeks to develop a strategic roadmap that aligns research with the evolving environmental sustainability needs and market demands.

Current status of forestry research in India,

Outline key areas of progress, challenges, and ongoing initiatives. This information reflects the state of forestry research as of my last update in April 2024, so some details may have changed since then.

- Institutional Framework:

– The Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education (ICFRE) remains the apex body for forestry research in India.

– It oversees nine research institutes and five centers spread across the country, each focusing on specific eco-regions.

– Other key players include state forest departments, universities with forestry programs, and the Forest Research Institute (FRI) in Dehradun.

- Priority Research Areas:

– Climate change mitigation and adaptation

– Biodiversity conservation and sustainable forest management

– Agroforestry and farm forestry

– Forest genetics and tree improvement

– Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) and their value chains

– Forest health, including pest and disease management

– Urban forestry and ecosystem services

- Technological Advancements:

– Increased use of remote sensing and GIS for forest monitoring and mapping

– Application of biotechnology in tree breeding and improvement

– Development of decision support systems for forest management

– Integration of AI and machine learning in various aspects of forestry research

- Collaborative Efforts:

– Growing number of international collaborations, particularly in climate change research

– Increased industry-academia partnerships for applied forestry research

– Enhanced cooperation between ICFRE and state forest departments for translating research into practice

- Challenges:

– Funding constraints for long-term ecological studies

– Gap between research outputs and field implementation

– Limited capacity in certain specialized areas (e.g., advanced genomics, big data analytics)

– Need for more interdisciplinary research approaches

- Recent Initiatives:

– National Mission for Sustaining Himalayan Ecosystem (NMSHE) with a significant forestry component

– Establishment of Centers of Excellence in specific research domains

– Launch of the National Forestry Research Plan (NFRP) to guide research priorities

– Increased focus on traditional knowledge integration with scientific research

- Publication and Knowledge Dissemination:

– Growing number of research publications in international journals

– Efforts to make research findings more accessible to practitioners through online platforms and mobile apps

– Regular national and regional conferences for knowledge sharing

- Capacity Building:

– Ongoing programs to train forest officers in the latest research methodologies

– Emphasis on developing a new generation of forestry researchers through fellowships and exchange programs

- Emerging Focus Areas:

– Forest-based bioenergy and sustainable products

– Ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction

– Urban forestry for air pollution mitigation

– Forest-water relationships in the context of climate change

- Policy Interface:

– Increasing emphasis on evidence-based policymaking

– Efforts to align forestry research with national and international commitments (e.g., NDCs under Paris Agreement, SDGs)

While India has made significant strides in forestry research, there’s a continued need for innovation, increased funding, and better integration of research findings into management practices. The sector is gradually moving towards more technology-driven, interdisciplinary approaches to address complex forest-related challenges.

Latest developments and innovations to fill the gaps in state forest department.

Outline of scientific points to address tailored for an audience of forest officers, scientists, academicians, and policymakers:

- Current State of Forest Research:

– Overview of major research areas: biodiversity conservation, climate change adaptation, sustainable forest management

– Recent advancements in remote sensing and GIS for forest monitoring

– Progress in understanding forest ecosystem services and their economic valuation

- Emerging Challenges:

– Climate change impacts on forest health and resilience

– Increased frequency and intensity of forest fires

– Invasive species and their effects on native ecosystems

– Balancing conservation with growing demands for forest resources

- Innovative Research Directions:

– Genomics and biotechnology for forest tree improvement

– Artificial Intelligence and machine learning applications in forestry

– Advanced modeling techniques for predicting forest dynamics

– Novel approaches to urban forestry and agroforestry

- Bridging Research Gaps in State Forest Departments:

– Enhancing collaboration between research institutions and forest departments

– Implementing adaptive management strategies based on research findings

– Developing standardized protocols for long-term ecological monitoring

– Integrating traditional ecological knowledge with scientific research

- Policy Implications:

– Evidence-based policymaking using latest research outcomes

– Aligning forest policies with international commitments (e.g., Paris Agreement, SDGs)

– Encouraging interdisciplinary research to address complex forest issues

– Promoting open data and knowledge sharing platforms

- Capacity Building:

– Upgrading skills of forest officers in latest research methodologies

– Fostering partnerships between academia and forest departments

– Establishing centers of excellence for specialized forest research

– Encouraging early career researchers through fellowships and grants

- Future Research Priorities:

– Developing climate-resilient forest management strategies

– Exploring nature-based solutions for climate change mitigation

– Advancing research on forest-based bioenergy and sustainable products

– Investigating the role of forests in human health and well-being

- Technological Integration:

– Leveraging big data analytics for forest resource assessment

– Implementing blockchain for transparent forest product supply chains

– Using drones and LiDAR for precise forest inventory and monitoring

– Developing early warning systems for forest threats using IoT sensors

Latest innovations in the forestry sector that could empower the forest department and foresters of Karnataka. Here are the list of some cutting-edge developments:

- Advanced Remote Sensing and GIS Applications:

– High-resolution satellite imagery: Karnataka can leverage the latest satellites like Cartosat-3 for ultra-high-resolution mapping of forest areas.

– LiDAR technology: This can provide accurate 3D mapping of forest structure, helping in biomass estimation and habitat analysis.

– Hyperspectral imaging: Useful for early detection of forest stress and disease outbreaks in Karnataka’s diverse forest types.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning:

– Species identification: AI-powered apps can help Karnataka’s field staff quickly identify plant and animal species using smartphone cameras.

– Predictive modeling: ML algorithms can forecast potential areas of human-wildlife conflict, allowing for proactive management.

– Automated change detection: AI can analyze satellite imagery to detect illegal logging or encroachment in real-time.

- Drone Technology:

– Forest fire management: Drones equipped with thermal cameras can detect hotspots and assist in firefighting operations in fire-prone areas like Bandipur.

– Seed dispersal: Drones can be used for aerial seeding in difficult-to-access areas, aiding in afforestation efforts.

– Wildlife monitoring: Silent drones can help in non-invasive wildlife surveys, especially useful in tiger reserves like Nagarahole.

- Genomics and Biotechnology:

– Climate-resilient varietals: Developing drought-resistant and disease-tolerant tree species suitable for Karnataka’s varying climatic conditions.

– DNA barcoding: This can help in tracking illegal wildlife trade by identifying the origin of confiscated animal parts.

– Assisted migration: Genetic techniques to help vulnerable species adapt to changing climates within Karnataka.

- IoT and Sensor Networks:

– Early warning systems: Deploying sensor networks to detect forest fires, landslides, or unusual animal movements.

– Water resource management: IoT devices to monitor water levels in forest streams and reservoirs, crucial for wildlife and nearby communities.

– Acoustic monitoring: Using sound sensors to track biodiversity and detect illegal activities like logging or poaching.

- Mobile and Web-based Applications:

– Citizen science apps: Engaging the public in biodiversity monitoring and reporting across Karnataka’s forests.

– Forest patrolling apps: GPS-enabled apps for more efficient and data-driven forest patrols.

– E-governance portals: Streamlining administrative processes like permit issuance and grievance redressal.

- Blockchain Technology:

– Timber traceability: Implementing blockchain to ensure the legality and sustainability of timber harvested from Karnataka’s forests.

– Carbon credit trading: Facilitating transparent and efficient carbon credit systems for forest conservation projects.

- Advanced Materials Science:

– Eco-friendly alternatives: Developing sustainable alternatives to plastic tree guards and other forestry equipment.

– Smart fencing: Using advanced materials for wildlife-friendly fencing to mitigate human-wildlife conflict in border areas of protected forests.

- Bioacoustics:

– Elephant early warning system: Using infrasound detectors to monitor elephant movements and prevent human-elephant conflicts in regions like Kodagu.

– Biodiversity assessment: Analyzing soundscapes to monitor ecosystem health and species diversity in less accessible areas.

- Climate Modeling and Adaptation Strategies:

– Microclimate mapping: High-resolution climate modeling to understand local variations and inform species-specific conservation strategies.

– Adaptive management tools: Decision support systems that integrate real-time data to guide forest management in a changing climate.

- Sustainable Ecotourism Technologies:

– Virtual reality experiences: Offering immersive forest experiences to reduce physical impact on sensitive ecosystems.

– Smart visitor management: Using AI to optimize tourist flow and minimize ecological impact in popular areas like Kabini.

By adopting these innovations, state forest departments can enhance its efficiency in conservation, improve data-driven decision-making, and better address the complex challenges of modern forest management. These technologies can empower foresters with tools to more effectively protect and manage the state’s rich forest resources while balancing ecological needs with socio-economic development.

Way to Meet NDC target by 2030

To increase tree cover and forests in India and meet the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target of 33% forest and tree cover by 2030, a multi-faceted approach is needed. Here are some key strategies and enabling factors that could help achieve this goal:

- Afforestation and Reforestation Programs:

– Large-scale plantation drives focusing on native species

– Restoration of degraded forests and landscapes

– Promotion of urban forestry and green corridors

- Agroforestry and Farm Forestry:

– Incentivize farmers to integrate trees into agricultural landscapes

– Develop and promote fast-growing, economically valuable tree species

– Provide technical support and extension services to farmers

- Policy and Legal Framework:

– Strengthen and effectively implement existing forest conservation laws

– Develop policies that incentivize private sector involvement in afforestation

– Align state-level policies with national forestry goals

- Community Engagement:

– Expand Joint Forest Management (JFM) initiatives

– Empower local communities through programs like Community Forest Rights

– Integrate traditional ecological knowledge into forest management practices

- Technology Integration:

– Use remote sensing and GIS for precise monitoring of forest cover changes

– Implement blockchain for transparent tracking of afforestation efforts

– Utilize AI and machine learning for optimizing plantation strategies

- Financial Mechanisms:

– Increase budgetary allocation for forestry sector

– Develop innovative financing models like green bonds for forest projects

– Streamline and expand CAMPA (Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority) fund utilization

- Research and Development:

– Invest in developing climate-resilient tree species

– Research on optimal species mix for different agro-climatic zones

– Study and enhance the carbon sequestration potential of different forest types

- Capacity Building:

– Train forest department staff in latest afforestation techniques

– Educate local communities on sustainable forest management

– Develop a skilled workforce for large-scale plantation activities

- Inter-sectoral Coordination:

– Ensure coordination between forestry, agriculture, and urban development departments

– Integrate forest conservation goals into infrastructure and development projects

- Private Sector Engagement:

– Encourage corporate sector participation through CSR initiatives

– Develop public-private partnership models for afforestation

- Sustainable Forest Management:

– Implement scientific management practices to enhance forest productivity

– Control forest degradation factors like forest fires and invasive species

- Green Infrastructure:

– Promote green buildings and vertical forests in urban areas

– Develop green belts around cities and industrial areas

- Monitoring and Evaluation:

– Establish a robust system for real-time monitoring of forest cover

– Regular assessment and reporting of progress towards NDC targets

- International Cooperation:

– Leverage international funding mechanisms like REDD+

– Collaborate with other countries for knowledge and technology transfer

- Public Awareness:

– Launch nationwide campaigns to educate the public about the importance of forests

– Encourage public participation in tree planting and conservation efforts

Enabling Factors:

- Political Will: Strong commitment from government at all levels

- Adequate Funding: Sustained and increased financial allocation for forestry sector

- Stakeholder Collaboration: Effective partnerships between government, NGOs, communities, and private sector

- Technology Adoption: Widespread use of cutting-edge technologies in forestry

- Policy Coherence: Alignment of various sectoral policies with forest conservation goals

- Land Availability: Clear land use planning and availability of land for afforestation

- Market Development: Creating markets for forest products to make forestry economically viable

- Climate Change Integration: Mainstreaming climate change considerations into forestry planning

To successfully implement these strategies and leverage the enabling factors, a coordinated effort from all stakeholders is crucial. The government needs to play a central role in creating an enabling environment, while actively involving communities, the private sector, and civil society organizations in the process.

Sidebar